n

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. I would go further by saying a single image can trigger a complex memory that’s not just visual; it can potentially involve all five senses. If that’s the case, can one then consciously use images to build instant and strong non-visual sensory associations? The answer is yes and we’ll explore in the text below. But first, let’s consider the common challenges facing students preparing for tasting exams. I’ve mentioned two of them above but here is a more complete list.

Major Challenges

- Old World New World style: is the wine fruit or earth-driven? Does the presence of earth and/or mineral elements dominate the wine or is said wine a shameless fruit bomb from the New World?

- Oak vs. phenolic bitterness: in a white wine, does the slightly bitter and astringent finish signify oak aging? Or is it phenolic bitterness from the wine having undergone limited skin contact pre-fermentation or during fermentation itself? If oak is the answer, then other markers such as spice, toast, vanilla, smoke, etc., will usually accompany the bitter sensation. If not, skin contact is the likely answer.

- Cool vs. warm climate: does the wine show restrained alcohol, high acidity, and tart/under-ripe fruit from a cool/cold climate? Or was the wine produced from grapes grown in a warm/hot climate offering ripe, even jammy fruit, high alcohol, and restrained acidity (which is usually adjusted).

Calibrating Structural Elements

- Acidity: how much? Is the wine flabby or closer to a liquid laser beam?

- Alcohol: how much? Does the wine show a lot of heat on the nose and palate or offer the barest trace of warmth?

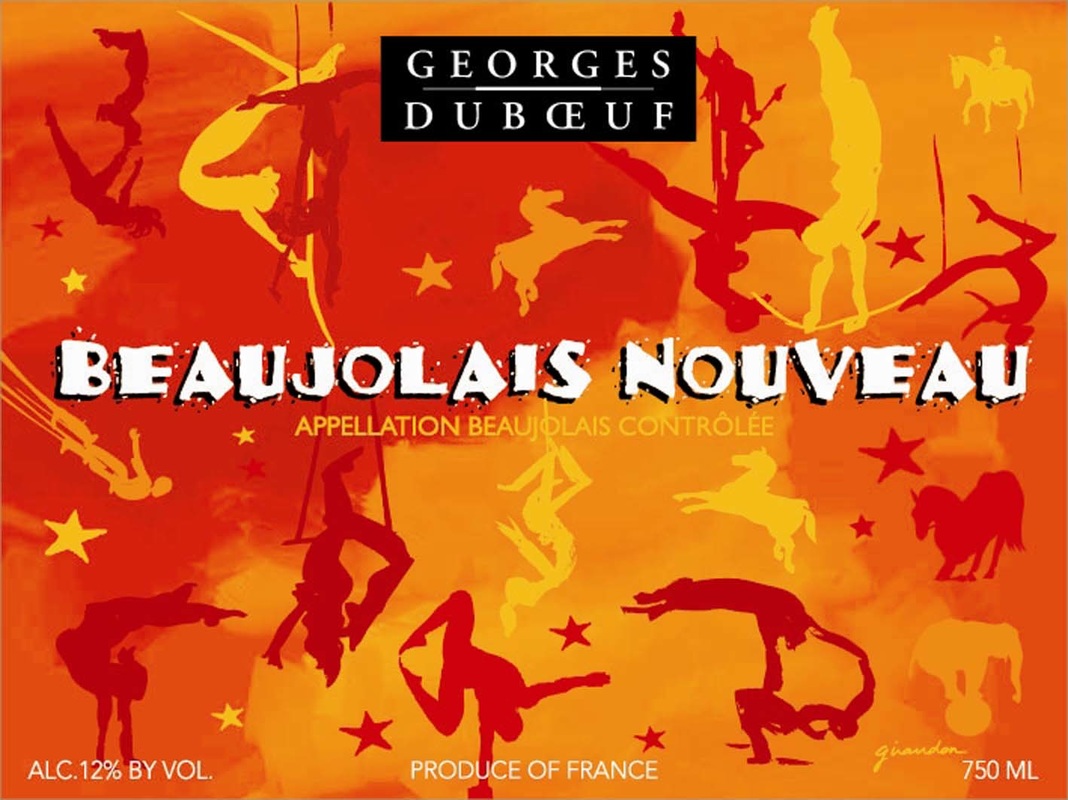

- Tannin: how much? Extremes in tannin are easy to find: Nouveau Beaujolais at the shallow end of the pool and a just-released vintage of Barolo at the deep end.

Recognizing Key Objective Factors

- Pyrazines: the green bell pepper, vegetal, herbal notes in Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet Family wines.

- Terpenes: the floral and sweet citrus aromas and flavors found in semi-aromatic grapes such as Chenin Blanc and fully aromatic grapes like Gewürztraminer.

- Rotundone: the peppery qualities found in Grüner Veltliner and Syrah.

- TDN: the gasoline/petrol notes found on the nose and palate of Riesling.

Maybe I’m lazy here but I want easy solutions to all the above. Pictures—the right pictures—are the easiest possible solution. By pictures I’m thinking of the labels of certain wines that offer extreme examples of all the criteria listed above. Labels that if brought to mind’s eye internally during one of the “moments of truth” mentioned above would trigger strong memories of the important aromatics/flavors listed above–and more importantly, provide an instant yes/no answer. I call it “Label Check.” Granted, this is anything but hard science but I’m operating on several presuppositions here:

First, over 90% of the human race is visual dominant internally. That is we tend to think in pictures and movies.

Second, calibrating using extremes is not only the easiest way to learn but to also to recall what was just learned. Example: if you can see black and white on opposite ends of a spectrum it’s easy to almost instantly find a shade of gray in the middle.

Third: as mentioned above, in keeping with the one picture/thousand word thing, a single image can have complex meaning for us involving all five senses. That’s important for us in the wine world.

Fourth: if anything else, when using an extreme example or polar opposite it’s easy to get to a simple yes/no answer—and in an instant. For our purposes, that’s extremely important.

There’s a method to my madness here: first, we’ll use extreme examples for all the criteria listed above in the form of specific labels to get an immediate yes/no answer. Then we’ll use the same strategy to calibrate sensory memory in terms the level of structural elements including acidity, alcohol, and tannin as well as important signatures in wine such as pyrazines and terpenes. Now for the instructions to the strategy:

Instructions

- Choose one of the elements/challenges mentioned above. For example, let’s use oak in white wine.

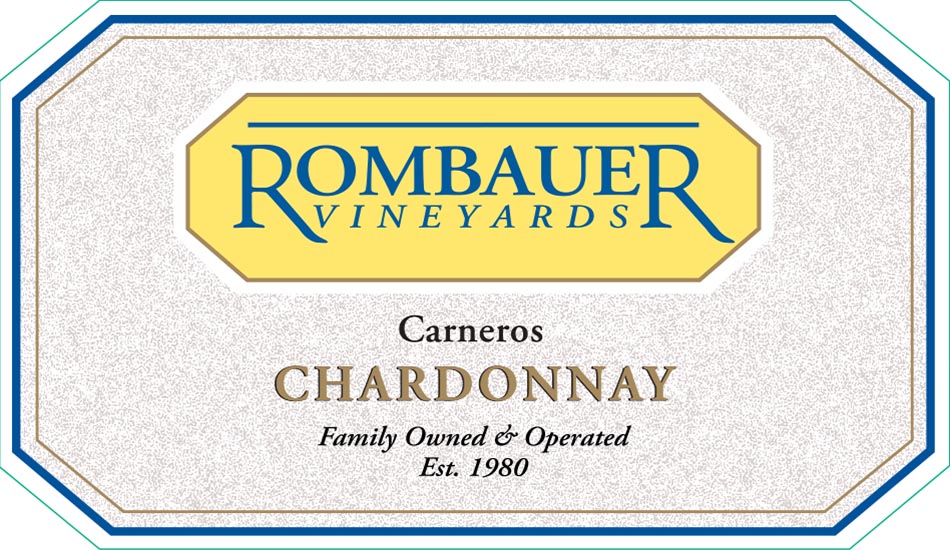

- Choose the label of a wine that represents an extreme example of new oak in white wine, in this case probably a pricey California Chardonnay. I’m thinking Rombauer here (See below).

- Once you choose a label bring it to mind.

- Make the label enormous in your mind’s eye out in front of you—five-by-seven feet will do nicely.

- Now make the label as bright as you can.

- As you look at the huge, bright label in your mind’s eye really get a sense of the wine in terms of new oak with aromas of strong vanilla, toast, spice and how all that smells, tastes, and feels on your palate.

- Now amp up your impression of the oak in the wine while looking at the label. Make it as strong as you possibly can in the moment.

- Repetition: practice several times or until you can bring up the label in mind and immediately get a strong impression of oak.

Application

Now it’s time to test the strategy. In your next tasting practice as you go through the grid with a white wine, when you get to the point of assessing oak, bring up the Chardonnay label, huge and bright in your mind’s eye and ask yourself, “Yes or no?” The answer will be immediate and practically always a strong “yes” or “no” with the exception in the case of used wood. But the important thing is that you can now detect oak precisely in the moment–and do so quickly. And that, meine freunden, is a very good thing. With that, here are suggested labels of wines that show an extreme of some kind that can be used in a similar fashion.

The labels I’ve chosen below are suggestions with which to work. By all means chose labels of wines you know best and that will create the strongest and most immediate memories and associations. Remember to choose the label of a wine that shows something to the extreme. Also, choose colorful labels; nothing boring unless it’s a no-brainer (as in Rombauer Chardonnay). Major Challenges

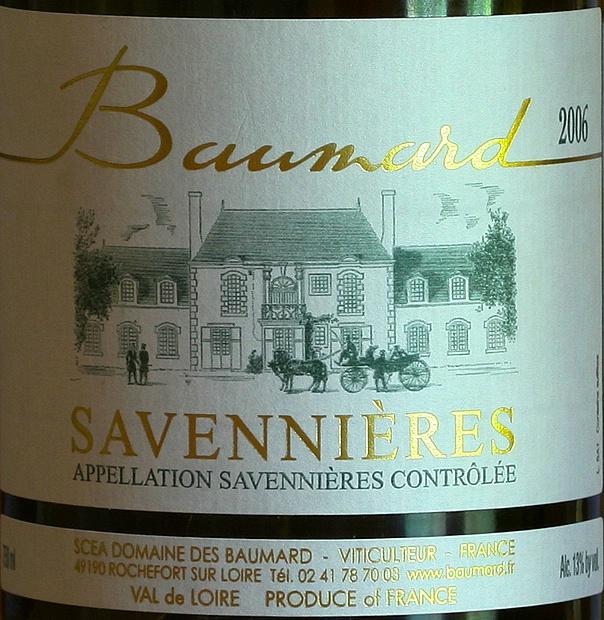

- Old World New World Style: Rombauer vs. Baumard Savennières

*Editor’s note: please get it through your craniums that I am not bashing Rombauer in any way. I think their Chardonnay is a fantastic example of what many consider “New World” white wine. Moving on. 2. Cool vs. warm climate: Moreau Chablis vs. Rombauer Chardonnay

California Chardonnay. High acidity vs. ripeness. Piece of cake.

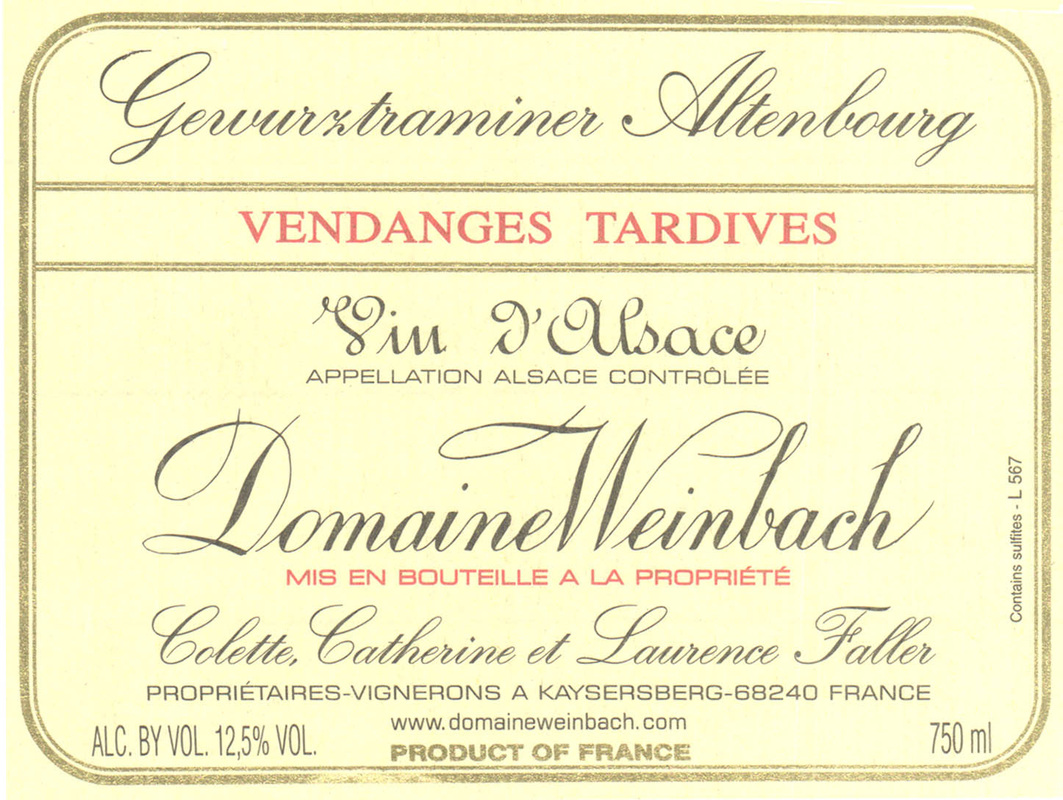

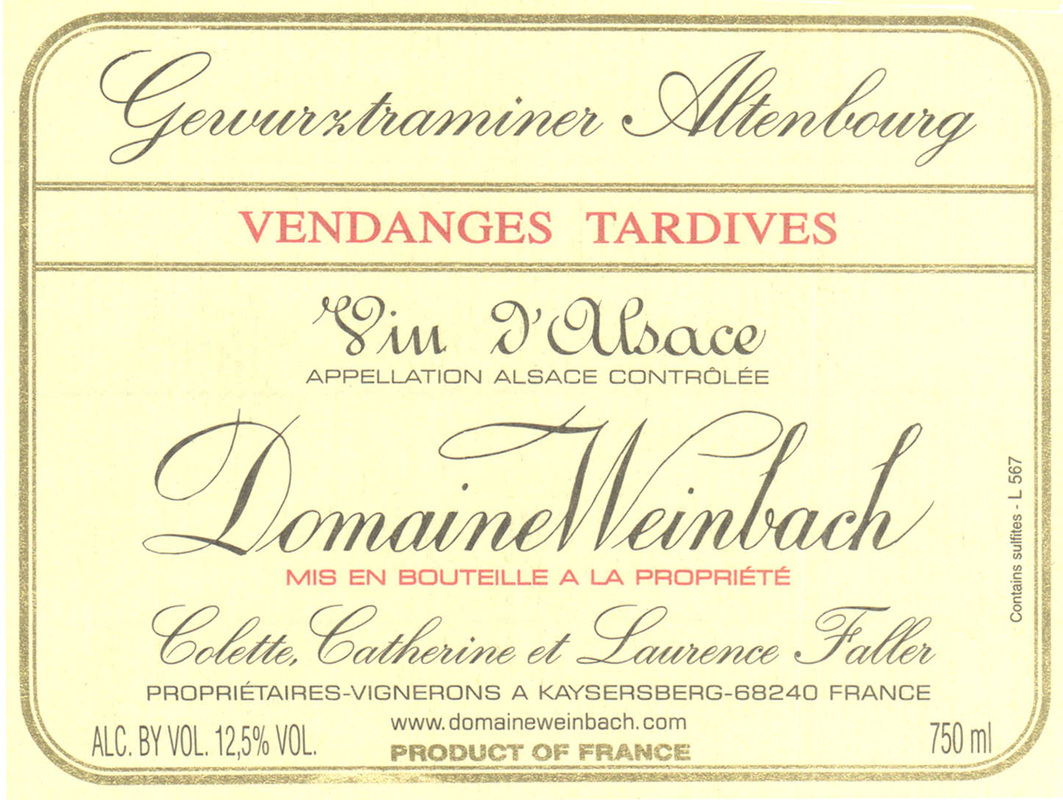

3. Mistaking Phenolic Bitterness for Oak: Weinbach Gewurztraminer vs. Rombauer Chardonnay

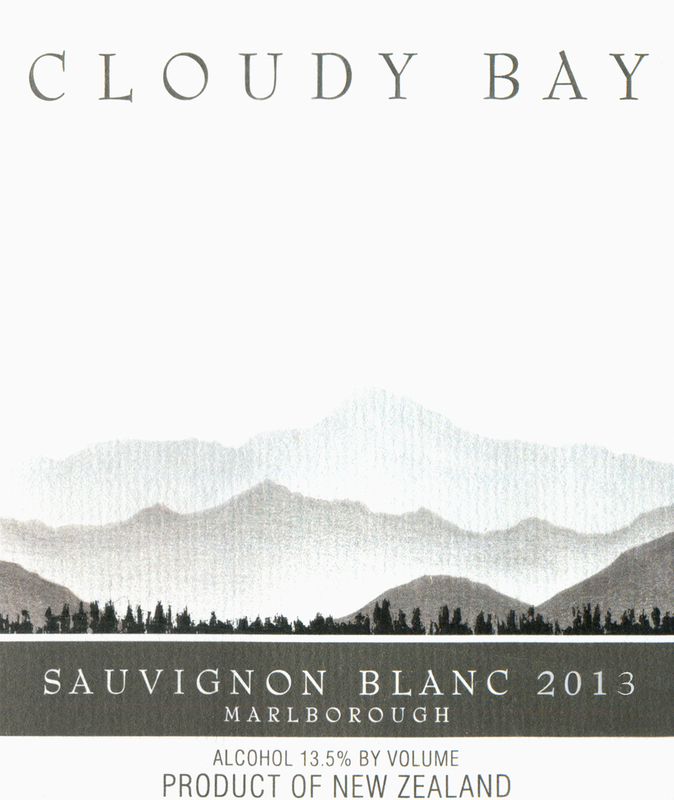

4. Recognizing Oak Influence: Cloudy Bay Sauvignon Blanc vs. Rombauer Chardonnay

Calibrating Structural Elements

In keeping with the idea of using labels of wines that show extremes, I want to reiterate that once you’re able to quickly calibrate “high” vs. “low” in terms of acidity, alcohol, or tannin, it will be just as easy to find “medium” much less “medium-minus” or “medium-plus.”

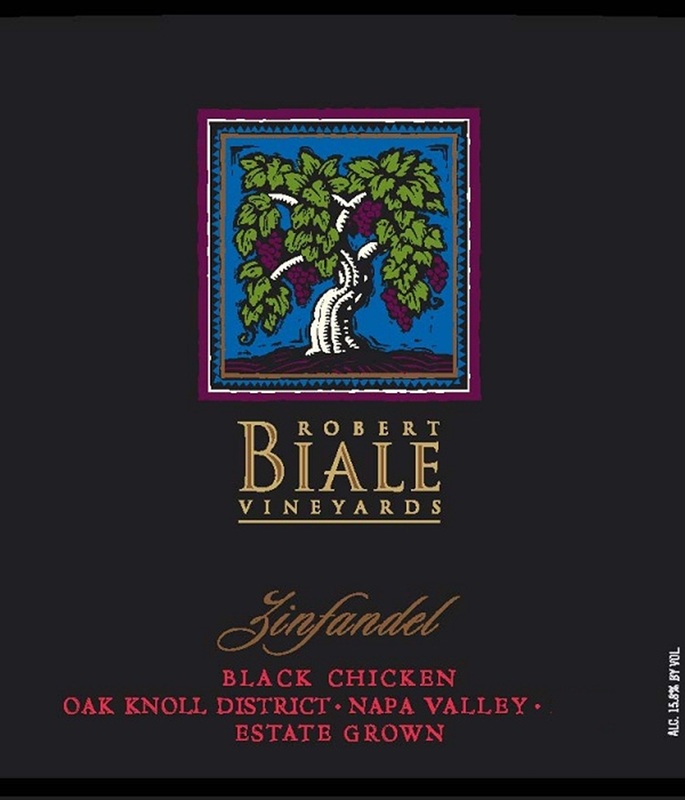

1. Alcohol: how much? J.J. Prüm Zeltinger Sonnenuhr Spätlese vs. Biale Black Chicken Zinfandel

2. Tannin: how much? Dubeouf Beaujolais Nouveau vs. Aldo Conterno Barolo “Bussia”

3. Acidity: how much? Weinbach Gewurztraminer vs. Baumard Savennières

Objective Factors

Beyond the above challenges and calibrating structural elements we can use the label strategy to help recognize important signatures in wine–key markers that are critical to identifying a many classic grapes and wines.

1. Pyrazines: Brancott Reserve SB

2. Terpenes: Colomé Torrontés

3. Rotundone: Graillot Crozes Hermitage

4. TDN: Grosset Riesling “Polish Hill,” Clare Valley

Final Thoughts

Play with the label check strategy. Once you get the hang of it labels can be used for any number of instant yes/no recognition moments needed during the tasting process.

One more thing… Once you get the instant recognition part of the label strategy down take it a step further using submodalities. By that I mean changing the structural qualities of your internal images of the labels. Specifically, practice making the label images smaller and larger in your mind’s eye. As you make them larger increase the intensity of the oak/phenolic bitterness/mineral/alcohol or whatever. As you make the images smaller decrease the intensity of your memory for said element. Reset the image/memory every time for consistency. You can build heightened sensitivity the aforementioned elements just by doing this alone.

Cheers!

nn