n

The Beginner’s Dilemma

Sound familiar? I think this is a common experience for most people just getting into wine. It was for me. I clearly remember going to my first professional tasting while in grad school studying music. As I stood next to a vendor’s table, with a taste of what I seem to recall was a Châteauneuf du Pape in my glass, I listened to the two guys who were next to me. They were waxing poetic about the wine saying things like baked earth, dried spice, and leather. I immediately put my nose back into the glass and it smelled like … red wine. Period. I thought the two guys were completely full of it or hallucinating—or both.

It wasn’t until several months later during the holidays that I had my first wine epiphany. A good friend had given me a bottle of 1976 Silver Oak Alexander Valley Cabernet for Christmas. It became my contribution to the holiday dinner we were sharing with a professor and his wife. The ‘76 vintage was one of several consecutive drought years in California, and the wine was rich, powerful, and quickly filled the room with aromas of blackberry jam and exotic spices once poured. It was the very first time that wine smell like things instead of just wine. I remember thinking, “this is what they’re talking about!” From then on, wine would never be the same.

What changed between experiences “A” and “B”? What was the key that made the difference between wine smelling like wine and wine smelling like other things? At the time it seemed completely mysterious and it wasn’t until decades later that I finally pieced together what had happened.

My experience points to one of the major wine disconnects–that wine as a fermented beverage can smell like a great deal of things which can confuse and/or intimidate the beginning taster. The answer to this conundrum may be as simple as perception and recognition, and developing and improving one’s olfactory and taste memory.

The good news is that practically everyone has all the hardware and software required to smell, taste, and remember. We’ve been doing it since we were infants. In fact, we are more than capable of storing a complex taste memory fairly easily. Not convinced? Take a moment to consider exhibit “A,” the humble cheeseburger. If we take the seven commonly referred to taste sensations as in sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami (savory), kokumi, and fat into consideration, the garden variety cheeseburger can check off on all the categories except for bitter–unless of course you’ve burned the burger or are being très chic by adding radicchio to the fixings. Combine these with other variables such as temperature, texture, and context (where, when, how and with whom you enjoyed said cheeseburger) and you have the makings (sorry for the pun) for a very complex smell and taste memory indeed.

I’ve written about the image-olfactory connection several times previously, but suffice to say that practically all the professional tasters—and students–I’ve worked with over the years use images in some form or another to identify aromas and flavors when they smell and taste wine. These range from two-dimensional internal still images all the way to multi-sensory panoramic life-size movies. At this point, I’ll go as far to say that if you can’t create an image for something you are smelling or tasting in a glass of wine, you probably won’t be able to recognize it.

Front Loading and the Basic Set

The challenge for the beginning taster (and teaching them) becomes clear: how to bring awareness to the connection between internal images and olfactory/taste memories. What’s important to note here is that we’re not talking about actual physical smell and taste, we’re talking about memory function. And if that’s the case, it’s possible to improve one’s memory—and recognition–without an actually having wine in hand.

In the past few years I’ve worked with a technique I call “Front Loading,” combined with a subset of the most common wine aromas I’ve dubbed the “Basic Set.” Front Loading in effect is working backwards to improve one’s memory of the most common elements found in wine—without using wine. Further, the Basic Set is comprised of the most common aromas and flavors found in a majority of all wines. I’ve found that using both in conjunction can bring awareness to the image-olfactory connection and ultimately improve tasting ability—in some cases considerably.

The Basic Set: Common Wine Aromas and Flavors

- Green apple

- Yellow/Golden Delicious Apple

- Pear

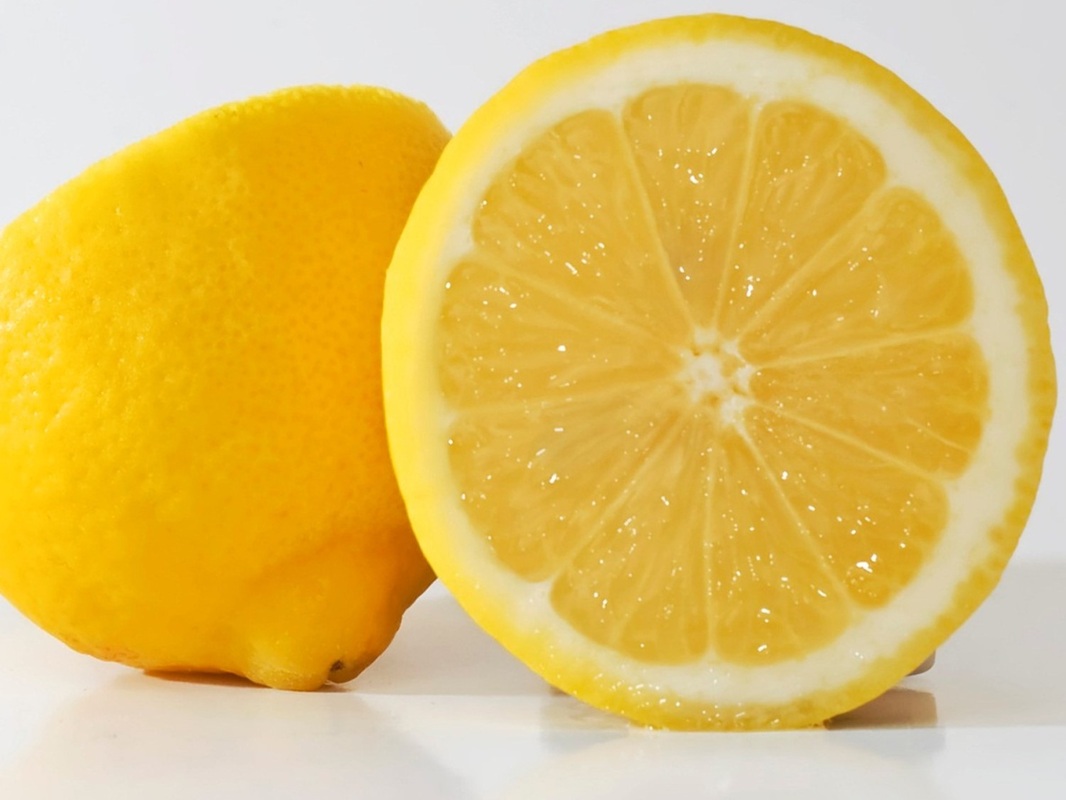

- Lemon

- Lime

- Orange

- Banana

- Peach

- Apricot

- Black Cherry

- Blackberry

- Red Cherry

- Cranberry

- Raisin/prune

- Roses

- Violet

- Mint/Eucalyptus

- Green bell pepper

- Rosemary

- Black/white pepper

- Vanilla

- Cinnamon

- Close

- Toast

- Coffee

- Chocolate

- Mushroom – forest floor

- Chalk

Using the Basic Set

There are four steps that can be used with the Basic Set. This sequence is designed to use a combination of visual and auditory in several ways to improve olfactory and taste recognition and memory. Here are the four steps:

I. Using external images and words

II. Using personal memories/internal images

III. Using submodalities to intensify memories

IV. Using internal images and contrastive analysis

Step I: Using External Images and Words

I’ve listed six images below:

- Lemon

- Lime

- Green apple

- Roses

- Vanilla

- Mushroom/earth

Using the images, do the following:

1. Look at the image and say the name of the fruit, etc. internally, or out loud.

2. Recall a time when you smelled and/or tasted the given fruit, spice, etc.

3. In your mind’s “eye,” reach out or pick up a slice of the fruit (etc.), and take a bite of it.

4. Make your experience of the fruit, spice, or other component as complete and intense as possible down to the aromas, flavors, texture, and mouthfeel.

5. Go through the list several times. It won’t take long. With each repetition, try to get to your memory of the fruit, etc., as quickly as you can and make your memory as complete and as intense as possible.

Now use your own memories to bring up the same aromas/flavors. As you bring up each memory, say the name of the fruit/spice, etc. either internally or out loud once again. Adding sound/auditory to your memory work not only reinforces each memory, but it provides other avenues—auditory and the physicality of speaking—to stimulate the memory. As before, make your experience of the fruit, spice, or other component as complete and intense as possible down to the aromas, flavors, texture, and mouthfeel. Practice the list several times. Once again, with each repetition see if you can get to the memory faster and more with more intensity.

- Lemon

- Lime

- Green apple

- Roses

- Vanilla

- Mushroom/earth

Step III: Using Submodalities to Intensify Memory

Submodalities are the structural qualities to our internal images, sounds, and feelings. It may sound complicated—but it’s not. Think about any of your memories which are visually-based. In your internal field, so to speak, the images all have a location, size, proximity, brightness, dimension, and more. Further, changing any one of the most important submodalities for visual such as size or distance, can dramatically change the intensity of the memory. With that, you can intensify the experience of your memories of lemon, lime, green apple, roses, vanilla and mushroom/earth by doing the following:

a. Make your images (or movie) larger

b. Bring your images closer

c. Make the colors brighter

Once again, as you play with the images, say the word for each internally or out loud. This step may take a bit of practice. Play with one submodality at a time. See which one intensifies the memory the most. For me, size and distance both change any visual memory dramatically.

Step IV: Using Images and Contrastive Analysis

Contrastive analysis is another way of saying “trying to put two things in the same place.” In this case, we’ll take your images of the aromas and or flavors from the list and play with them. The results at the very least will be curious. Here are the instructions. Use your images/memories for the pairs of elements listed below.

- First, be aware of the location where each image/memory lives in your internal “theater.”

- Next, try to put one of the images exactly where the other is located.

- Be aware of what happens to the images when you try them both in the same location.

I: Lemon and mushroom

II: Lime and vanilla

III: Orange and rose

What happens when you try to move one image on to another? Practically everyone I’ve done this exercise with (self-included), experienced something akin to placing polarized magnets near each other. The images usually fly apart and become separated by a noticeable distance–and the two images land in very specific locations where they naturally live in your “mind’s eye.”

While this exercise may seem initially odd, the same phenomenon will really come into play when one builds more complex “progressive” memories of specific grapes and wines. Then an Alsace Riesling will occupy a specific location and proximity in one’s internal field making it more difficult to confuse for another grape or wine—even another Riesling. But I’m getting ahead of myself …

Parting Thoughts on Using the Basic Set

• Repetition is key: work with the images/words dozens of times until your memories become automatic. It won’t take long to go through several repetitions.

• Remember the goal is to be able to bring up a memory of one of any of the elements completely and intensely–on command!

• Don’t limit your work to the Basic Set. Expand your repertoire to include as many other aromatics/flavors as you can.

• In time, start to put the components together in groups or sequences to form markers for classic grape and wines.

nn