n

They’re something every serious wine geek owns but rarely, if ever, mentions to outsiders. No one would understand. We take pains to transport them great distances home only to store them on dark, dusty shelves. In my case some live in a basket in my living room but most are tucked away in an old cardboard box in the garage. What are these mysterious things? Rocks. That’s right, rocks.

Aside from a geologist whose livelihood is completely dependent on all things subterranean, no other profession I can think of involves a compulsive desire to collect rocks, even dirt. But wine geeks do exactly that. When on the road in some distant wine locale your average wine geek will reach down to scoop up bits of soil and rocks of varying sizes (sometimes ludicrously large) only to deposit them (rock joke) into jeans pockets and backpacks ultimately to be hidden in luggage to make the long trek home.

Why rocks? Better yet, why would anyone in their right mind drag a bunch of rocks thousands of miles home in their suitcase? There is no one answer. Once in the deep end of the pool wine geeks can and often do get a bit carried away–even compulsive–about the great wine places they visit. A rock from an important region can be a powerful connection to a time and place where hopefully one really “gets” a wine. And for many wines there is no more meaningful symbol of place than the rocks that make up part of the physical landscape. In effect, a single rock can be a very effective memory and learning device.

I’m also convinced there are wines and regions that one can never truly understand unless one actually spends time in said place; that unless you physically stand in the vineyard with a glass of wine in hand you’ll never fully get the place much less the wine. Jerez and Sherry are a perfect example as are Burgundy and obviously Germany. A lot of it has to do with looking at the ground not to mention the aspect of the vineyard, the region’s altitude (Mendoza, anyone?), the intensity of sunlight, and so on. Rocks once again are front and center.

I clearly remember my MS Introductory Course in March of 1990, the second such class ever taught in the U.S. At the time pterodactyls still roamed the sky and primitive man was first starting to decant for aeration purposes. I digress. During the Burgundy lecture Brian Julyan, head of the UK chapter of the Court, passed around a sizable chunk of limestone he pilfered from the Le Clos vineyard to illustrate the terroir of Chablis. He accompanied the limestone chunk with a photo of the slope in Chablis that is home to all the Grand Cru vineyards, then went on to emphasize certain points about the unique minerality of Chablis

vis–à–

vis its soil using typed notes on an overhead projector. That’s right, an overhead projector. I wasn’t kidding about the pterodactyls.

In a recent post I put forth the notion that certain ancient vineyards—as in vineyards that are centuries, even millennia old—could be considered sacred spaces. By that I mean vineyards whose history and singularity qualify them as world heritage sites and beyond. I feel strongly about this. Take the Wehlener Sonnenuhr vineyard in the Mosel which has been cultivated sans interruption for over 2,000 years. Rieslings from the Sonnehuhr site with its bluish gray Devonian slate formed over 150 million years ago are arguably the most delicate and refined of all the wines produced in the Middle Mosel. The “soil” which is composed entirely of crumbling slate, is not only a major factor of the vineyard’s history but a vital part of the wine’s character as well.

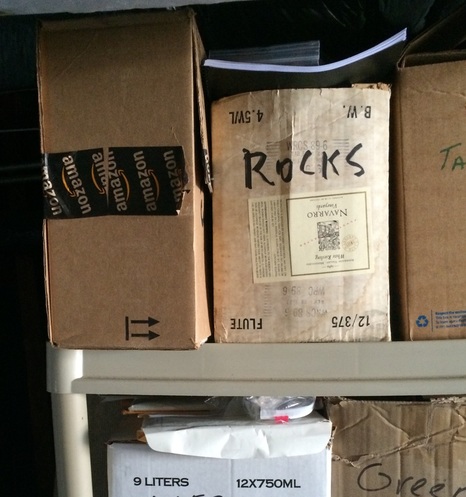

Like others I have my own collection of rocks. Here is a trio—and their stories–from my personal collection. All hold great significance and wonderful memories for me.

I. Santorini and Volcanics: Paris Sigalas and His Remarkable Assyrtikos

Assyrtiko Vines on Santorini

September, 2006; the legendary MS tour of Greece. Ten days of seeing literally every part of the country that has anything to do with wine; an average four-plus hours a day in a van driven by a young Greek lad who wore the same synthetic disco shirt the entire trip thereby redefining the concept of localized terroir. The highlight of highlights was visiting the island of Santorini, surely one of the most beautiful spots on the planet. On the windier leeward side of the island Paris Sigalas and his crew tirelessly care for old Assyrtiko vines that are pruned close to the ground into round basket-like shapes called ampellari. I have a vivid memory of our group standing in the late afternoon sun with Sigalas and his winemaker. Paris repeatedly mentions the terroir pointing at the ground which is covered with a proliferation of volcanic rocks of every kind including chunks of whitish pumice so light in the hand they’re almost weightless. We head back to the winery to taste verticals of oaked and un-oaked Assyrtiko. The experience is revelatory. Sigalas’ unoaked Assyrtiko is one of a kind because of its great depth and richness with considerable alcohol—often up to 14.5%–balanced by ferociously high natural acidity. But the hallmark of all his wines is the minerality which is completely off the charts. There probably is no better example of volcanic minerality in any wine made anywhere. On the palate the mineral quality is so incredibly strong it feels grainy like black pepper—minus the black pepper. I took several rocks from the vineyard and they live in the basket in my living room. Today when I hold them for a few seconds I’m instantly transported back that late afternoon bathed with golden Mediterranean sunlight standing in Sigalas’ vineyard looking at the arid, windswept vines in their odd basket shapes. I can smell and taste his exotic Assyrtiko as vividly as if I was actually there. The feeling is remarkable.

II.The Middle Mosel and Slate: Electric Rieslings from the Bernkasteler Doctor

The Doctor Vineyard with the Village of Bernkastel Below

May, 2002; my third trip to the Mosel. It’s early evening and the fourth and last winery stop for the day. By now the residual sugar and intensely high acidity from dozens of wines has managed to fry the palate of everyone in the group including mine. Since early morning we’ve been tasting wines from the superb 2001 vintage that’s just been put in bottle. But the best of the day was saved for last. We’re visiting Weingut Wegeler in Bernkastel with winemaker Norbert Breit as our host. After meeting us at the small winery just off a narrow cobblestone street in the village we’ve taken the steep and winding drive hundreds of feet above the river to the very top of the legendary Doctor vineyard. Breit pulls a newly minted bottle of 2001 Doctor Spätlese from his leather bag, opens, and pours. From there he really doesn’t need to say anything else. Wines from the Doctor vineyard, widely considered the best in the Mosel and easily in the top five in all of Germany, are known for their remarkable concentration, precision, and opulence. The 2001 doesn’t disappoint. It’s one of the greatest young German Rieslings I’ve ever tasted. Standing on shifting dark slate I looked down the perilously steep slope with the tiny village below and the river snaking away in the bright late afternoon sunlight. Then I reached down to pick up a chunk of dark slate that is somewhere between a large paperweight and a primitive weapon in size only to take another sip of the utterly delicious Riesling. It’s nectar of the gods. Vineyard-wine connection made; game, set, match.

III. Red Hills AVA and Obsidian: The Future of California Cabernet?

Beckstoffer’s Cabernet Vineyards in the Red Hills AVA

In early May of this year I spent time in Lake County with Bob Bath, MS. It was my first visit there in many years and I was quickly reminded of how unique the place is. Clear Lake is not only the oldest lake in California but also its largest body of fresh water. The average vineyard elevation is over 2,000 feet, easily the highest in California. That puts the area’s vineyards on course to be later for everything including flowering, bud break, véraison, and harvest. The combination of wide diurnal shift, high elevation, intense UV sunlight, and mineral-laden soils makes for wines of exceptional purity of fruit, high acidity, and—dare I say it—pronounced terroir.

Lunch the first day of our tour was hosted by Andy Beckstoffer at his vineyard house. Beckstoffer needs no introduction. One could argue that he is the most influential individual in California viticulture over the last several decades. The Beckstoffer name is closely associated with some of the industry’s top wines and vineyards. Over ten years ago Beckstoffer became convinced of the potential of Red Hills. He was the force behind the AVA’s genesis and made considerable investment in the area to the tune of 1,200 acres under vine all planted to Cabernet. To meet him we drove through dozens of acres of Red Hills Cabernet where the soil is a bright reddish-brown and littered with countless pieces of obsidian ranging in size from pebbles to a Fiat 500.

Before lunch Beckstoffer sets up a blind tasting of a half dozen Cabernets, 50/50 from Napa Valley/Red Hills. We quickly taste and take notes. When the wines are revealed the Napa bottlings are generally more polished but the Red Hills wines more than make up for it with an intense mid-palate mineral quality, something I infrequently experience in California Cabernet. Other common denominators for the Red Hills wines include intense varietal fruit, high natural acidity, restrained alcohol, and the just-mentioned tsunami of stone-mineral quality. My conclusion? With a few notable exceptions the winemaking isn’t quite there, but the raw material is exceptional—even world-class. It’s only a matter of time.

nn