n

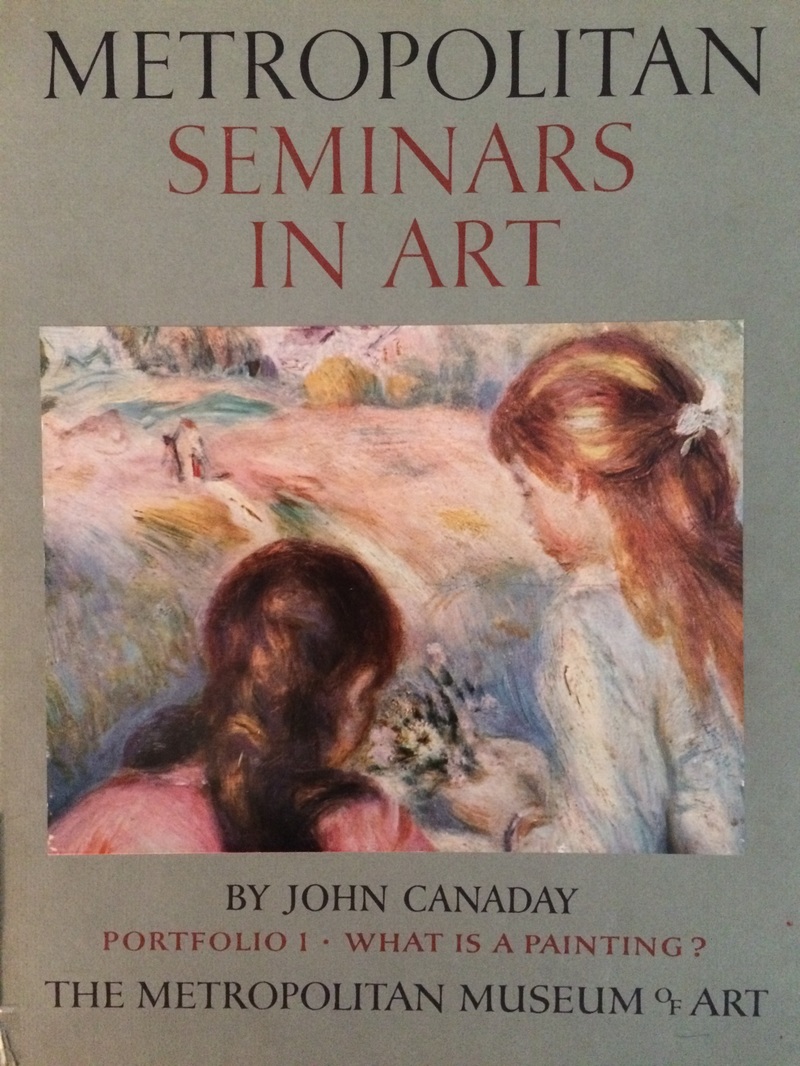

I have many memories of sitting with him looking at the reproductions of great paintings printed on thick glossy stock that accompanied each volume. I recall him saying dozens of times that this or that painting was “beautiful” or “gorgeous” or “amazing.” I also clearly remember him tell me emphatically, “this is important. Art is important. It’s one of the greatest things man has ever done.” Mind you, I didn’t connect with him on many levels so these two exceptions—music and art—quickly became near and dear.

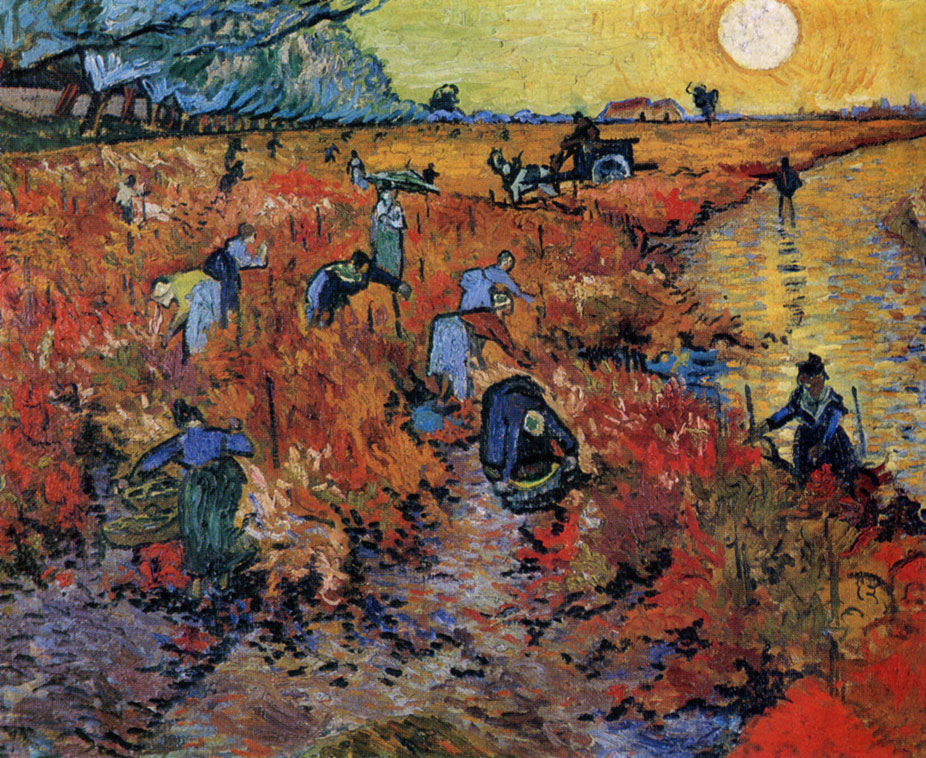

I love Impressionist art for how it represents nature and people in nature so subjectively, an enormous departure for painting at the time. With the use of remarkably beautiful colors and nuances of light and shadow, much of what is conveyed on the canvas is implied but not precisely depicted. The artist has left it up to the viewer to fill in the spaces internally and each of us does so uniquely and very subjectively. It’s as if Impressionism is the indirect communication of the art world.

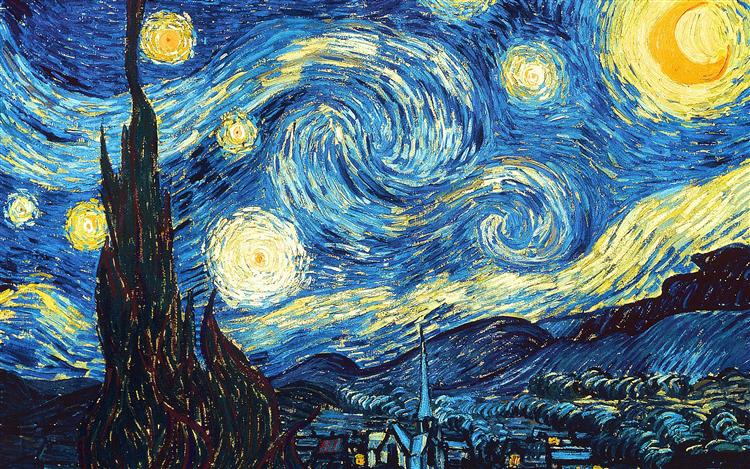

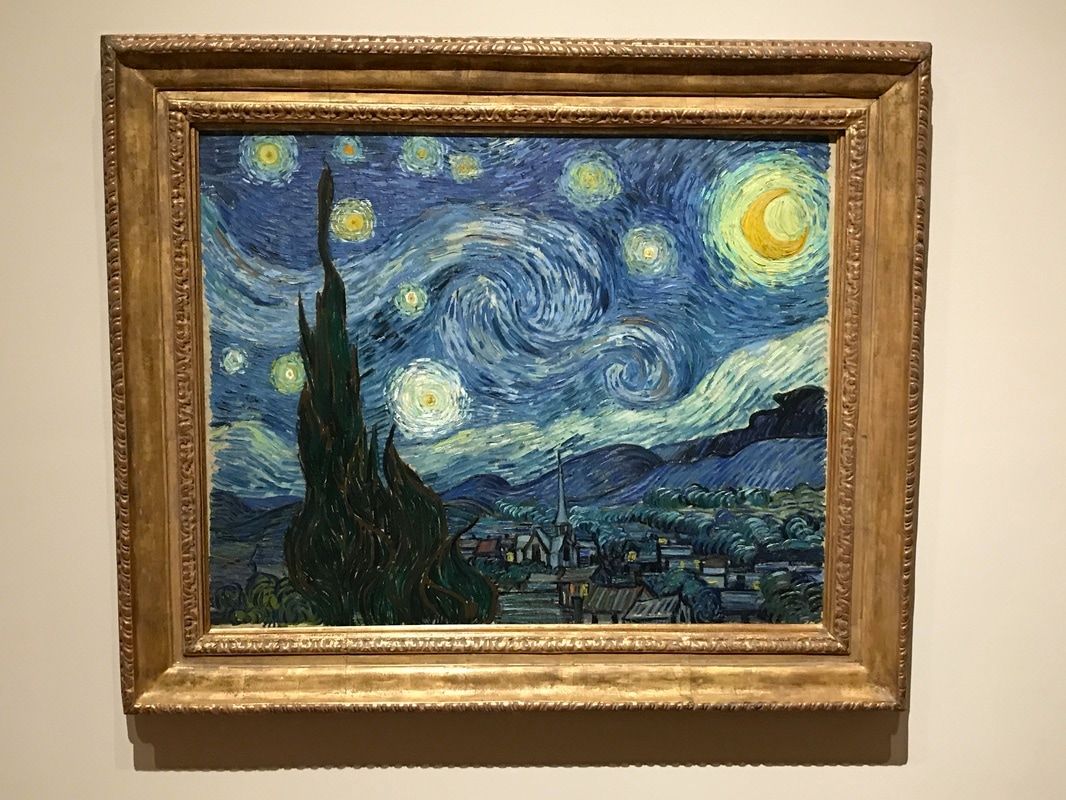

Van Gogh’s work, “Starry Night,” completed in 1889, is the one painting that immediately comes to mind. Though technically Post-Impressionist, Starry Night continues to astound with its dramatic use of color, intensity of emotion, and almost shocking application of paint on the canvas. The creative energy that became Starry Night can only be described as electric. Looking at the work today we get the slightest glimpse into what was the tumult of Van Gogh’s inner world.

Daniel Levitan is a Stanford-trained psychologist who also has a successful career as a recording engineer and producer. In his book, “This is Your Brain on Music,” he combines both disciplines to explore how the brain and our thought processes can be profoundly influenced by listening to music. He writes:

“Much of what we see and hear contains missing information. Our hunter gatherer ancestors might have seen a tiger partially hidden by trees, or heard a lion’s roar partly obscured by the sound of leaves rustling much closer to us. Sounds and sights often come to us as partial information that has been obscured by other things in the environment. A perceptual system that can restore missing information would help us to make quick decisions in threatening situations. Better to run now than sit and try to figure out if those two separate, broken pieces of sound were part of a lion’s roar.”

Levitan writes further that the great perceptual psychologist Hermann von Helmholz calls this process, “unconscious inference,” a way of saying that “what we hear and see is the end of a long chain of mental events that give rise to an impression, a mental image, of the physical world. Many of the ways in which our brains function—including our senses of color, taste, smell, and hearing—arose due to evolutionary pressures, some of which no longer exist.”

What does Impressionism in art and unconscious inference in music have to do with wine? Good question. I’ve often thought about the role that expectation plays when looking at a glass of wine. How our memory of previous wines in terms of color, texture, and other aspects creates expectations when looking at a “new” glass of wine; literally how we fill in the blanks with a new glass of wine using previous information. I’ve also questioned the value of previous experience when looking at a new glass of wine. Should we allow previous memories to influence expectations? Or should we attempt to view each new glass of wine as a separate and unique experience without drawing on previous memories as a more accurate way to experience, much less assess?

Several years ago I had a long conversation with a good friend and industry colleague who said that she always tried to approach each wine as a totally new and unique experience; that she wanted at all costs to avoid judging a new wine based on previous experience. I respected her viewpoint but also immediately wondered if it was actually possible given the concept of unconscious inference mentioned above.

Personally I’m a firm believer in the value of previous experience when it comes to looking at a glass of wine. To a seasoned taster the simple act of tilting the glass forward to have a close look at a wine can—and should—build instant expectations with regards to a wide range of criteria; from possible grape variety to climate of origin to fruit character (fresh, dried, tart, etc.) and most importantly the structural elements including potential levels of acidity, alcohol, and tannin. For example, looking at a glass of red wine that’s lighter in color can build instant expectations in terms of a thinner-skinned grape variety grown in a cooler climate with red fruit dominating the palate and the structure of the wine offering less alcohol, higher natural acidity, and moderate tannins.

No doubt that this is all far from hard science. One can always be surprised when actually smelling and tasting a wine when initial expectations aren’t met. But drawing from one’s previous experiences can be considerably useful in blind tasting practice and exams, not to mention mental/associative rehearsal of classic grapes and wines. Given that, here are four scenarios with possible expectations as well as thoughts on secondary colors in red wine and the potential information derived from the legs-tears.

Light/pale color =

- Youth

- Possible cooler climate/vintage

- Possible anaerobic fermentation

- Lack of new oak aging

- Possible lighter body

- Possible less alcohol

- Possible higher natural acidity

- Tarter—less ripe—fruit quality

Deep yellow or gold color =

- Warmer climate/riper vintage

- Oxidative winemaking/overall age

- Possible extended aging in new oak

- Possible botrytis

- Possible phenolic bitterness

- Possible higher alcohol

- Possible lower natural acidity with potential for acidulation

- Riper fruit quality

Lighter Color =

- Thin skinned grape

- Cooler climate/vintage

- Less overall ripeness

- Red fruit dominant

- Possible higher natural acidity

- Possible lower alcohol

- Possible less overall tannin

- Possible more non-fruit elements

Deeper color =

- Thicker skinned grape

- Warmer climate / vintage

- Dark fruit dominant

- More overall ripeness of fruit

- Possible less non-fruit elements (fruit-dominant wine)

- Possible higher alcohol

- Possible lower natural acidity with potential for acidulation

- Possible higher tannin

- Possible residual sugar

- Extreme cases: less varietal definition

Pink or purple color =

- Youth

- Lack of extending oak aging

Salmon/orange/yellow/brown =

- Age in barrel or bottle and/or oxidative winemaking

- Possible thin skinned varieties (i.e., Sangiovese, Pinot Noir, Nebbiolo, Grenache)

Quickly forming, thinner and quickly moving tears/legs =

- Lower alcohol

- Possible cooler climate

- Lack of residual sugar

Slower forming, thicker and slower moving tears/legs =

- Higher alcohol

- Warmer climate growing region

- Possible presence of residual sugar

- Higher dry extract

Staining of the tears in red wines =

- Thicker skinned grape

- Concentrated wine

- Possible warmer climate

- Higher dry extract

nn